Monty Hall & Probability

This article is the combination of a series of posts I made on LinkedIn.

Part 1 - Marilyn was Exactly Right

Monty Hall game. Three cards dealt face down -- 1 ace 2 jokers. Pick one, dealer (who knows where the ace is) flips 1 and reveals a joker. You can keep your card, or switch for the remaining card. What's your move?

It can feel like 50/50 (e.g. "doesn't matter") at first but it's not. You pick from 3 unknowns with 1 winning possibility and your odds are 1/3. That means 2/3 chance the ace is in the set of cards you didn't pick. The dealer just showed you one of those cards. Stay and your 1/3 chance doesn't change. Swap and your chance increases to 2/3. Why?

It's easier to see with more cards. Let's use 6, so it's like rolling a die. Dealer flips joker (always) from the remaining 5. Four cards left -- stay or switch? Stay and you've got 1/6 chance. Switch and you pick from 4 cards in a set 5/6 likely to contain the answer. Your odds? 5/6 * 1/4 = 5/24.

Always switch, and pick from a filtered set much more likely to contain the answer. The more cards dealt, the less it helps you, but it can never be as bad as the 1/n you take if you stay. The 3 card case? There's only 1 item in the filtered set, so your chances are (2/3) * (1/1) = 2/3. Our brain skips past the 1/1, making the collapsed probability mass harder to see.

When Marilyn vos Savant published this answer, thousands (including mathematicians) wrote angry letters insisting it was 50/50.

Incidentally, it doesn't matter if you pick your card or are assigned one. The choice is an illusion. Assume you pick and we rearrange to keep your card close to you. With available cards unknown this is no different than 'you get first card'. This simple game leads to surprising insights about probability, decision-making, and risk, with more to come in upcoming posts.

Part 2 - Why You Should Always Switch

Monty Hall Game Part 2. Last week we saw an illustration of Marilyn vos Savant's insight -- that switching doubles your odds when the dealer knows where the ace is -- you pick from a smaller set more likely to contain the answer, and you can't do as badly as the 1/n odds you accept if you stay.

What if it's random? What if you're sure the dealer has no special knowledge but just flips at random? Then it doesn't matter, right? Staying and switching are irrelevant. If the dealer is in fact truly random this is true. But how sure are you? Do you accept that there is any possibility that you are wrong? If you do, then you always improve your odds by switching.

The real question is not "what are my odds in this specific and potentially artificial scenario", it is "which action gives me the best expected outcome across all plausible scenarios?".

Consider this: if the dealer knows and always reveals joker, switch wins 2/3, stay wins 1/3. If dealer is random and happens to flip a joker, I've got 2 cards 2 unknowns, 50/50. Switching is the dominant strategy. It can't hurt but it can help.

Now, a tiny edge doesn't always matter. If switching gave you 1/240 better odds of winning a paperclip, who cares? But Monty Hall has a special structure: the cost of switching is zero. When an action costs nothing, any positive expected value, no matter how small, makes it the correct choice.

This is how I think about engineering decisions. Is that circuit off? Probably. Cost of checking? Seconds. Cost of being wrong? Potentially fatal. Are there API keys in the codebase? Almost certainly not. Cost of a CI/CD scan? Trivial. Cost of a breach? Catastrophic.

If an action has asymmetric risk, no downside with significant potential upside -- take it. Always switch.

Part 3 - k-flip Paradox

Last one in the probability series that emerged from Monty Hall. First, we saw an intuitive way to understand why switching helps (pick from filtered set). Second, why you should always switch (asymmetric risk) and how it applies to decision making.

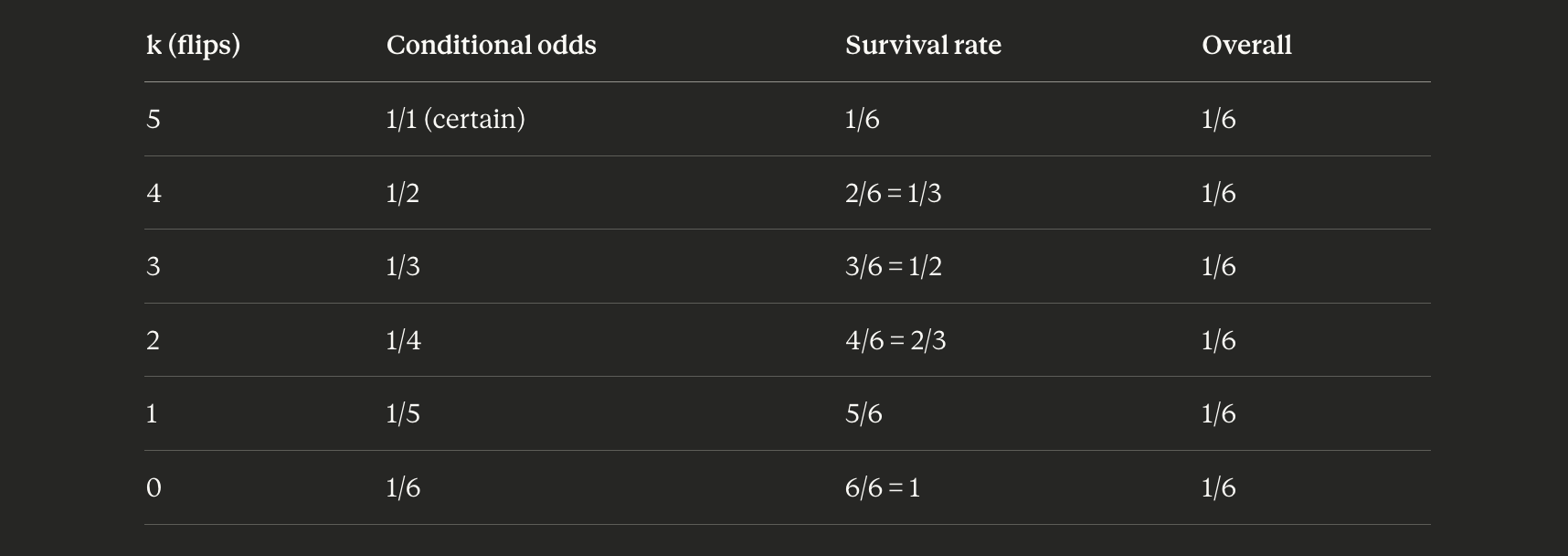

Finally? A real paradox, or at least a counterintuitive observation. It doesn't matter how many cards a random dealer flips. Your odds are always 1/n. See the table for details.

More flips gives you a lower survival rate, but better odds if you do. Six cards with dealer flips 4? Only 2 cards remain (dealer removed 2/3 of them). You do get a 50:50 chance, but only 1/3 of the time. 1/2 * 1/3 = 1/6. Dealer flips all but 1? If you're still alive you always win at that point, but it only happens 1/6 (== (n-k)/n) of the time.

Randomness is randomness, no matter how you shuffle it.